|

The Monistic Theory

by Nhân Tử Nguyễn Văn Thọ

TOC |

Preface | Chapters:

1 2

3 4

5 6

7 8

9

10 11 12

13 14

15

16 17

18 19

Chapter 16

Confucianism and the Monistic Theory

Confucianism gets

its name from Confucius (the Anglicized pronunciation of Kung-Fu-Tzu

which means "Kung the Teacher"). It was one of the great religions that

have dominated China, and its satellites, such as Japan, Korea,

Mongolia, and Vietnam, for more than two thousand years.

Confucius : The

Teacher-Standard of All Eternity (Wan-shih shih-piao :

萬 世 師 表)

Brevity shall be

the primary consideration in the life of Confucius. Suffice it to

mention that he lived from 551 to 479 B.C., almost at the same time as

Zoroaster in Iran, Ezekiel in Israel, Pythagoras in Greece, Lao-Tzu in

China, and Buddha in India.

" The Confucian

literature, as traditionally conceived, consists of the so-called Five

Classics and Four Books.

"The Five

Classics: Book of Rites, Book of Change, Book of History, Book of

Poetry, and Spring and Autumn Annals- were, with one exception, in

existence before Confucius's time. But they were edited by him and his

followers, so that, in the form in which they appear, they definitely

reflect a Confucian perspective.

"The exception is

the Spring and Autumn Annals, a history of the Chou era from 721 to 481

B. C. which has traditionally been ascribed to Confucius himself.

"The Four Books

are the more distinctively Confucian sources. Foremost among them is the

Analects-disconnected sayings of Confucius that were preserved by his

disciples.

"Then there are

the Golden Mean and the Great Learning- expanded chapters from the Book

of Rites, as interpreted by Confucius and refracted through the

understanding of his early followers.

"These two books

are collections of essays on basic Confucian themes, such as the

Superior Man, the Nature of true manhood, the significance of ritual, of

education and of music, the art of government, the moral order of the

universe.

"The last of the

Four Books is the Book of Mencius, containing the doctrines of a great

Confucian thinker who lived two centuries after Confucius. Mencius' work

comes closest, of these varied materials, to exemplifying what the West

would expect in a systematic moral and religious philosophy.

Confucianism and the Monistic Theory

Confucius,

according to his own words, did not create a new religion, but only

handed down the religion and the doctrines as practiced and taught in

the remote antiquity, by ancient Chinese Holy Sovereigns.

He did not create

a new line of politics but displayed only politics and regulations as

applied by the emperors of ancient times.

He did not create

any new convention and institution, but endeavored only to find out and

to conform to natural laws.

In other words,

he only fostered what is ideal, pertaining to religion, moral, and

politics, and promoted what is universal, eternal and natural.

It is said in the

Doctrine of the Mean: "Chung Ni handed down the doctrine of Yao and

Shun, as if they had been his ancestors, and elegantly displayed the

regulations of Wan and Woo, taking them as his models. Above, he

harmonizes with the lines of Heaven, and below he was conformed to the

water and land (Doctrine of the Mean, Chap. XX).

To find out the

religious life of the ancient China, we must therefore refer ourselves

to ancient Sovereigns of China, such as:

Yao (Nghiêu;

2757-2255 B.C.).

Shun (Thuấn;

2255-2205 B.C.)

Iu (Đại Võ,

2205-2197 B.C.)

Wan (Văn Vương;

1258?- ? B.C.)

Woo (Võ Vương;

1122- 1115 B.C.)

We can say

ancient, if we figure that the Flood occurred, according to some

Christian books, at about 2400 B.C., that Abraham lived around 1800 and

Moses around 1200 B.C.

We must also

survey a historical period spanning over almost two thousand years

before Confucius.

It points out

some very important religious features: Chinese people, then, believed

in God, considering Him as a creator, a judge and a sovereign who rules

the world through the agency of Holy Kings, named Sons of God. (Cf. Book

of Poetry, and Book of History).

God was in the

Heaven, but at the same time, He was very close to people, helping them,

protecting them, conducting them and chastening them if necessary. It is

said in the Book of Poetry:

" Revere

the anger of God,

And

presume not to make sport or be idle.

Revere

the changing moods of God,

And

presume not to drive about (at your pleasure).

Great

God is intelligent,

And is

with you, in all your goings.

Great

God is clear seeing,

And is with

you in your wanderings and indulgences."

We can also

illustrate this closeness of God with people, by two other historical

traits:

a). When King Woo

(Võ Vương) confronted the immense army of the tyrant Shou (Trụ Vương),

in the wilderness of Muh (Mục Dã), the slogan to raise his morale and

the morale of his soldiers, was "GOD IS WITH YOU, have no doubts in

heart".

b). After the

battle, Shou (Trụ Vương) fled to the "Stag Tower" (Lộc Đài) and burned

himself to death. In the mean time, Woo (Võ Vương), having received the

congratulations of the princes on his victory, pressed on after the

tyrant. On arriving at the capital, the people were waiting outside the

walls in anxious expectations, which the king relieved by sending his

officers among them with the words: "Supreme God is sending down

blessings". The multitude reverently saluted the king, who bowed to them

in return, and hurried onto the place where the dead body of Shou (Trụ)

was".

Moreover, the

Ancient Holy Sovereigns believed that God was really present in their

soul. For them, God was really their essential and true nature and their

changing phenomenal soul was only a veil or at most an expression of

God. It is said in the Shoo King:

"The

human Self is restless and changing

The

divine Self is very recondite,

Realize

purity,

Realize

Oneness,

Stick to your Central Self."

Thus was the

profession of faith of the Holy Kings, two thousand years B. C.

Talking plainly,

we say:

"Under the

changing garb of our human self, there is a Divine Self, recondite

indeed, but nevertheless real. It serves as our kernel, our ground, our

Central Self. Recognizing this essential and divine nature, we perfect

our self, purify our self, and realize oneness with this Central Self."

In other words,

man's ultimate goal is to become perfect, to be united to God, recondite

in his own soul, and to become an expression of God.

King Wan (Văn

Vương) was so called because he was so virtuous that he was in fact

considered as an expression of God. (The She King, Decade of King Wan,

Ode 1, 7, p. 431).

Confucius, when

his life was endangered, when he was surrounded by the people of K'wang

(Khương), claimed also that his was really an expression of God, exactly

as King Wan. He said: "After the death of King Wan, was not the

expression (of God) conferred to me? If God has wished to let his

expression perish, then I should not have got such an honor. While God

does not let his expression perish, what can the people of K'wang do to

me?" (Analects, IX, 5).

Commenting on

Confucianism, Father Mateo Ricci, a Jesuit who came to China to preach

Gospel, at the XVIIth century, has written:

"I have noted

many passages (of their Scriptures) that are in favor of our faith, such

as the unity of God, the immortality of the soul, the glory of the

Blessed ones, etc".

Father Lecomte

(1655-1728) was more enthusiastic:

"The Chinese

religion, seems to have conserved intact and pure, in the course of the

ages, the primary truths revealed by God to the first human being.

China, happier than any other country in the world, has drawn almost

from the fountain-head, the holy and primary truths of its ancient

religion.

"The first

emperors built temples to God and it is not a small glory to China for

having sacrificed to the Creator in the most ancient temple of the

world. The primary piety is conserved in the people thanks to the

Emperors who endeavored to maintain it, so that idolatry could not

penetrate in China."

But the Roman

Catholic Church has condemned all these views.

The first

emperors referred to, were:

Hwang Te (Hoàng

Đế; 2697-2597 B. C.)

Yao (Nghiêu;

2357-2555 B.C.)

Shun (Thuấn;

2255-2205 B.C.)

Iu (Đại Võ,

2205-2197 B.C.)

Wan (Văn Vương;

1258-? B.C.)

Woo (Võ Vương;

1122-1115 B.C.)

It is worth to

note that these emperors lived before, or at least, at the period of the

Biblical Flood, and much longer before Abraham (1800).

In the

metaphysical standpoint, Confucianism, through the agency of the I Ching

(D¡ch Kinh), sustained that everything is rooted in God and has sprung

out from God.

After

multifarious changes and mutations through time and space, after a long

dialectical and cyclical movement of expansion and contraction, of

extroversion and introversion aimed at its fulfillment, everything will

return to God as its original soul.

This is called

the theory of Cyclical change (Tian di xun huan zhong er fu shi: Thiên

Địa Tuần Hoàn, Chung Nhi Phục Thủy).

God is then the

quintessence of everything, and the unifying principle of the universe.

He is transcendent, at the same time immanent in everything. The

phenomenal world consequently is only various expressions of this

essential Being, exactly as the eight trigrams or the sixty four

hexagrams are various expressions of the Wu Chi (Vô Cực) or T'ai chi

(Thái Cực).

For Confucius,

God, and the perfection of God, is in the Center of everything. The aim

of our study is to find out this Center, this Kernel. It is said in the

beginning of the Great Learning: "What the Great Learning teaches is to

brighten the mirror of the Conscience; to renovate the people; and to

rest in the highest perfection. The point where to rest being known, the

object of the pursuit is then determined; and that being determined, a

calm unperturbedness may be attained to. To that calmness there will

succeed a tranquil repose. In that repose there may be careful

deliberation, and that deliberation will be followed by the attainment

of the desired end.

"Things have

their roots and their branches. Affairs have their end and their

beginning. To know what is first and what is last will lead near to

Religion.

"The ancients who

wished to let their Conscience shine throughout the kingdom, first

ordered well their own States. Wishing to order well their States, they

first regulate their families. Wishing to regulate their families, they

first cultivate their persons. Wishing to cultivate their persons, they

first rectify their hearts. Wishing to rectify their hearts, they first

sought to be sincere in their thoughts. Wishing to be sincere in their

thought, they first extended to the utmost their knowledge. Such

extension of knowledge lay in the Discovery of the Kernel of everything.

The Kernel of

everything being discovered, knowledge became complete. Their knowledge

being complete, their thoughts were sincere. There thoughts being

sincere, their hearts were then rectified. Their hearts being rectified,

their persons were cultivated. Their persons being cultivated, their

families were regulated. Their families being regulated, their States

were rightly governed. Their states being rightly regulated, the whole

kingdom was made tranquil and happy.

"From the Son of

God down to the mass of the people all must consider the cultivation of

the person the root of everything besides." (Cf. J. Legge, The Great

Learning, p. 358-359).

The Kernel of

everything is also called The Eternal Center (Trung Dung), The Center

and Equilibrium (Trung Chính), the Supreme Summit (Thái Cực), the One

(Nhất), or The Eternal Religion (Trung Đạo). Names can vary, but the

Idea remain the same.

This idea of God

as origin, sustainer and indweller of the universe and of the human soul

is similarly expressed many times in the Upanishads.

According to the

Indian Upanishads, The Great Self or Person is the eternal axis which

keeps the universe in being. He is God who controls the world from

within, the ground on which all existence is woven.

Applied to man,

this cosmic view helps to solve the enigma of the human sphinx.

Instead of being

composed of body and soul as sustained by Christian theology, man

according to Confucianism, is tripartite. He has: A divine Self (Sing,

Tính) or spiritual Self. A psychological or human Self (Sin, Tâm). A

corporeal or material self (K'io, Xác)

He is then a real

microcosm reflecting the macrocosm. This tripartite conception of man,

denied by Christian theology, is however amazingly contained in the Old,

as well as, in the New Testament.

In the Bible,

Spirit and Soul are referred to as two different entities. The Spirit is

designated by the term Ruah in Hebrew, Pneuma in Greek and Spiritus in

Latin. The Soul is designated by Nephesh in Hebrew, Psyche in Greek and

Anima in Latin.

This tripartite

conception of man is clearly referred to by St Paul in 1 Thessalonians,

5, 25. "May the God of peace himself sanctify you wholly; and may your

spirit and soul and body be kept sound and blameless at the coming of

our Lord Jesus Christ. (I Thess. 5, 23). In The Epistle to Hebrews, St

Paul considered Spirit and Soul as two different entities. He said: "For

the word of God is living and active, sharper than any edge sword,

piercing to the division of soul (Psyche) and Spirit (Pneuma). (Hebrews,

4, 12)

Freud, on his

own, has also recognized three factors in man behavior: The Id or the

animal self, The Ego, The Superego.

The Superego can

be compared with the Spirit. It is also what Carl Jung has called the

Collective Unconscious, and William James has called the Mystical or

Cosmic Consciousness.

Now, if we put

aside our corporeal body, that everyone can easily experience, we

realize that the master-key to unlock the mysteries not only of

Confucianism, but also of all great religion in the world, is the

"Spirit and Soul Theory".

a)- According to

Confucianism, the Spirit or our true nature (Sing; Tính), is in fact

divine. It is the "Divine Spark" (Ming te; Minh Đức) referred to in the

Great Learning; the Nature (Sing; Tính) referred to in the Doctrine of

the Mean. Mencius sustained therefore that this Nature is truly good.

It is also

nothing else than our Moral Conscience, where all the moral laws are

written by God.

The Book of

Poetry said:

"God is

giving birth to the multitude of the people,

To every

faculty and relationship annexed its law.

The

people possess this normal nature,

And they consequently love its normal

virtue"

The Doctrine of

the Mean sustained that the model of perfection is not to be

far-fetched. It can be found in our own Spiritual Self.

"Therefore, the superior man governs

man according to their nature, with what is proper to them, and as soon

as they change what is wrong, he stops".

This assertion

reminds us of one similar passage in the Deuteronomy, where God, after

giving the Ten Commandments to Israel, has said: "For these commandments

which I command you this day is not too hard for you, neither is it far

off. It is not in heaven, that you should say: Who will go up for us to

heaven, and bring it to us, that we may hear it and do it? Neither it is

beyond the sea, that you should say: Who will go over the sea, for us

and bring it to us, that we may hear it and do it? But the word is in

your mouth, and in your heart, so that you can do it!" (Deuteronomy, 30,

11-14)

That also reminds

us of one passage of Jeremiah: "But this is the covenant which I will

make with the house of Israel after these days, says the Lord: I will

put my law within them, and I will write it upon their hearts..."

(Jeremiah, 31, 33)

b). On the other

hand, the soul or our Ego is human, and consequently imperfect. It

should be educated, chastened and harnessed to become perfect. Our soul

can be dissipated easily by external agents. This is what Confucianism

called the loss of the soul. Mencius complained that people are losing

their soul and do not know how to seek for it. He said: "When men's

fowls and dogs are lost, they know how to seek for them again, but they

lose their soul and don't know how to seek for it. The great end of

learning is nothing else but to seek for the lost soul. (Mencius, VI, I.

11)

The true

religion, for a Confucian, is then the quest for this Divine Self, the

gradual realization of this Divine Self. Mencius said: "All things are

already complete in us. A conversion inward for self-fulfillment will

give us a highest pleasure" (The work of Mencius, Book VII, Pt. I, Chap.

4).

Conversion is

then man's turning back to his truest nature. Wang-Yang-Ming (Vương

Dương Minh), another Confucian philosopher of a later period (1472-1529)

sustained the same view. "Every man, said he, has an inborn Divine mind,

which is our Spiritual Self, namely our moral Conscience. The moral

Conscience is the same in the sage and in the fool. The difference

resides in that the sage keeps the conscience clear and fulfill himself

according to its directives, while the fool obscures it and neglects its

suggestions".

The SPIRIT-SOUL

Theory can be proved by the teachings of any great religion.

Buddhism has the

Buddha-Nature (Dharmakaya) and the Illusory Ego.

The Quran accepts

also a threefold state of man: The Physical State or Nafs-Ammara. The

Moral State or Nafs-Lawwama. The Spiritual State or Nafs-Mutmainnah.

Taoism has the

Tao and the Human Soul.

St Paul referred

to a Psychical Body, and a Spiritual Body in his first Corinthians (I.

Cor. 12, 44).

Ancient Greek

philosophers distinguished the "Nus" or Divine Mind from the "Psyche" or

the Soul.

Hinduism has the

Atman and the Individual Soul theory. In the Chandogya Upanishad, The

Atman is referred to as "this Soul of mine within the heart is smaller

than a grain of rice, or a barley-corn, or a mustard-seed, or a grain of

millet, or the kernel of a grain of millet; this Soul of mine within the

heart is greater than the earth, greater than the atmosphere, greater

than the sky, greater than these worlds. Containing all worlds,

containing all desires, containing all odors, containing all tastes,

encompassing this whole world, the unspeaking, the unconcerned-this is

the Soul of mine within the heart, this is Brahma. Into him I shall

enter on departing hence. If one would believe this, he would have no

more doubt." (The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Robert Ernest Hume,

I988, Printed in India, 3, 14.)

To illustrate

these two parts radically different but at the same time merged

together, Tagore resorts to "the dewdrop and the sun-ray" parable.

The dew-drop

complains to the sun: "I am longing for you, but never I dare nourish

the hope to serve you. I am to little to attract you, O almighty God,

and in all my life I will be tearful! The sun replies: "I am

illuminating the immense sky, but I do take care of the small dew-drop.

I will be a light ray, and will overwhelm Thee, and thy life will be a

world of brightness. (Nguyễn Đăng Thục, Lịch Sử Triết Học Đông Phương,

III, p. 10)

We can sum up

these preceding ideas as follows:

God is not far

from man. He is very close to man, not only close, but resides in fact

in the innermost of the human soul.

The true human

nature partakes to the nature of God.

Human nature, as

well as human destiny, is then sublime.

The insight of

the relationship between God and man helps Confucius to understand the

true destiny of man.

According to

Confucius, man should use his life for self-perfecting in order to reach

the highest state of perfection, rendering him worthy to be united to

God. At the same time, he should also help other people to cultivate

themselves and to perfect themselves.

"Consequently,

the basic concern is no longer the struggle for life, for the precarious

requisites of continued physical existence, it is instead the quest for

the good life, for the finest moral and spiritual realization of which

man is capable under the complex condition that a civilized society

confronts".

It is said in the

beginning of the Doctrine of the Mean:

"What

God has conferred, is called the Nature,

The

realization of this Nature is called Religion.

The

illustration of this Religion, is called Instruction.

This

Religion may not be severed from us even for an instant.

If it

could be severed, it would not be the Religion."

And a little bit

further:

"Our Central Self

or Moral Being is the great basis of existence, and harmony or moral

order is the universal law in the world. When our true Central Self and

harmony are realized, the universe then become a cosmos and all things

attain their full growth and development."

Chu hsi (Chu Hi),

commenting on this first chapter of the Doctrine of the Mean, has said:

"This religion is to be traced to its origin, to God, and is

unchangeable, while the substance of it is provided in our self and may

not be departed from...The learner should direct his thoughts inward and

by searching in himself, there find these truths so that he might put

aside all outward temptations appealing to his selfishness, and fill up

the measure of the goodness which is natural to him ".

A true Confucian,

believing that God is immanent and present in his soul, will behave

himself always very properly. "Going out of home, he is reverent as if

he has to welcome a distinguished guest; in dealing with people he is

respectful as if he is performing a ritual ceremony."

Alone, he is furthermore careful and

reverent, venerating Him who is invisible, fearing Him who is inaudible,

but from Whose view nothing is left unsighted.

The quest for the

Divine is then at the same time, the quest for self-fulfillment.

God, being

immanent in our soul, the model of perfection is also contained in our

innermost self.

Consequently, the

Great Learning consists of discovering this divine nature; the noblest

duty of man is to rekindle this Divine Spark latent in him.

The

self-fulfillment should be rooted in this transcendental discovery,

because only the discovery of one's own divine nature can truly help man

to transform himself and fulfill himself completely.

Translated into

Christian language, it means that the Kingdom of God is not far, it is

already within us (Mat. 3,2.- Luke 17,21)

This knowledge

and this fulfillment begins from the innermost of an eminent man and

will irradiate and propagate themselves to other people, from the

family, to the nation, from the nation to the world, for the benefit of

the whole mankind.

The essential

rule of conduct of a superior man is the imitation of God. (The I Ching,

Chien hexagram, the Image.)

Now if perfection

is the lot of God; the attainment of perfection is the lot of man.

It is rather

amazing to note that five hundred years later, Jesus Christ has taught

to humanity the same lesson:

"You therefore,

said he, must be perfect, as your heavenly father is perfect". (Mat. 4,

48)

According to the

Doctrine of the Mean, Goodness, Knowledge and Energy are three cardinal

virtues leading to perfection.

It is said in the

Doctrine of the Mean:

"He who desires

to attain to perfection, is he who chooses what is good, and firmly

holds it fast.

" To this

attainment, there are requisite the extensive study of what is good,

accurate inquiry about it, careful reflection on it, the clear

discrimination of it, and the earnest practice of it.

"The superior

man, while there is anything he has not studied or while in what he

studied there is anything he cannot understand, will not intermit his

labor.

"While there is

anything he has not inquired about, or anything in what he has inquired

about which he does not know, he will not intermit his labor.

"While there is

anything which he has not reflected on, or anything in what he has

reflected on, which he does not apprehend, he will not intermit his

labor.

"While there is

anything which he has not discriminated, or his discrimination is not

clear, he will not intermit his labor. if there is anything which he has

not practiced or his practice fails in earnestness, he will not intermit

his labor.

"If another man

succeed by one effort, he will use a hundred efforts. If another man

succeed by ten efforts, he will use a thousand.

"Let a man

proceed in this way, and though dull, he will surely become intelligent,

though weak, he will surely become strong" .

We realize, then,

that to increase our goodness we should fulfill all our duties required

by our stations in life and apply the Golden Rule towards other people;

that to increase our intelligence, we should keep on inquiring,

studying, and thinking through all our life, and that to increase our

will power, we should have the sense of emulation and strain after a

perfect life.

The religious

life starts, then, from the reverent feeling of the presence of God in

man's soul, develops itself through the progressive blooming of all our

potentialities and ends in the complete union with God.

James Legge in

his commentaries of the Doctrine of the Mean, has written: "Between the

first and the last chapters, there is a correspondence, and each of them

may be considered as a summary of the whole treatise. The difference

between them is that in the first, a commandment is made with the

mention of God as the conferrer of man's nature; while in this the

progress of man in virtue is traced step by step till the last, it is

equal to that of God.

According to the

Great Learning, our life should be devoted to rekindle the divine spark

in our self, to renovate people and to tend towards the highest

excellence (The Great Learning, Chap. 1)

We are advised by

Confucius to study the Book of Poetry to know how to enjoy and

appreciate all the beauties revealed by nature and men.

We should study

the Rites, to know all the natural laws and good procedures embodied in

good manners and ceremonials.

We should study

Music so that we can harmonize ourselves with other people and with the

cosmos. (Confucian Analects, VIII, 9)

Understanding

that though apparently petty and humble, man has in fact a very noble

destiny, that man can have a good life here and that God is always

present in the human soul to direct man through the voice of the

conscience, Confucius felt himself overwhelmed with joy. He said: "If

man in the morning hear the true religion, he may die in the evening

without regret." (Analects, IV, 8).

Fortified by his

faith, he could also say: "With coarse rice to eat, with water to drink,

and my bent arm for a pillow, I have still joy in the midst of these

things. Riches and honors acquired by unrighteousness are to me a

floating cloud." (Analects, VII, 15).

Only this

religious faith could explain why even being in the distress, in the

wilderness between Chan (Trần) and Ts'ai (Sái) regions, Confucius could

take his lute and sing to it (Lin Yutang, the Wisdom of Confucius, p.

81), and why he could spend many years in propagating the new faith

without fluctuations.

His activities

remind us of Romain Rolland's saying: "I feel in me a strong faith, I

should share this faith to whom in need. I will make a revelation to my

people, I will be a pioneer. No matter if the world will destroy me or

pierce me. May I only rekindle this faith in others and in me.

To cultivate

one's soul in order to be united to God is also the ultimate goal of all

religions.

This ultimate

goal can be forsaken by the followers of religions, but it is

nonetheless, treasured in their sacred Scriptures.

In John's Gospel,

Jesus Christ has prayed many times for this oneness with God not only

for him but for all.

It is said in the

Quran: "And if my servants ask thee concerning Me, tell them that I am

very near them. I listen to the supplications of supplicators, therefore

they ought to seek my union with prayers and believe in me, so that

proceeding aright they may arrive at fulfillment. "

And again:

"Verily we are God's and verily to Him shall we return."

Tagore has said:

"The Infinite for its self-expression comes down into the manifoldness

of the finite and the finite for its self-realization must rise into the

unity of the Infinite. Then only is the cycle of the truth complete.

(Creative Unity)

The Buddha has

taught people how to forsake the illusory Ego and to realize the

Reality, how to sprung from the Temporal into the Eternal, from the

Phenomenal which is Samsara into the Noumenal which is Nirvana.

Buddhism too has

been a stumbling-block to Western religious thinkers; for Buddhism is

undoubtedly a religion, and in its primitive form it is undoubtedly

atheistic, at least in the sense that we normally understand the world.

But though the Buddhist Scriptures lay such tremendous emphasis on the

impermanence of all things, there are passages enough to show that over

against this ever-changing world the Buddha saw something that did not

change, over against Prakriti he saw Purusa though he would not have

formulated this thus.

He calls it

"deathlessness, peace, the unchanging state of Nirvana, or more clearly,

he says: "There is, monks, an unborn, not become, not made,

uncompounded. If there was not such a state of unborn, not become, not

made, uncompounded, no escape could be shown here, for what is born, has

become, is made, is compounded, therefore an escape can be shown for

what is born, has become, is made, is compounded."

Taoism has also

fostered this unitive life and sustained that the union with God was the

highest religious form in the Antiquity.

Confucius

realizing this common aim of humanity, has exclaimed: "In nature, all

things return to their common source, and are distributing along

different paths; through one action, the fruit of a hundred thoughts are

realized."

In brief, for

Confucius,, our life should be ordained spiritually, morally,

physically, individually and socially so that we can realize human

perfection.

For that, we

should have a sound idea about our true nature. We should be convinced

of our eminent destiny. We should be enthusiastic and persevering in our

quest for our self-fulfillment and the divine life. We should obey all

nature laws, and should develop all our potentialities. We should

cultivate not only our spirit and our soul but also our mind, our body,

our environment so that everything will become perfect.

We can never

emphasize enough that, for Confucianism, the norm of perfection is

already in the inmost of our soul. If we desire to work for our own

perfecting, we have only to act in conformity with this internal norm,

which is our moral conscience. According to Wang Yang Ming (1472-1529),

the Perfect Ones are perfect only because they obey this celestial norm

and get rid of all human passions.

Now if we desire

to imitate the Perfect Ones, we have only to eliminate all our selfish

passions and to maintain in us the celestial norm.

"Later

generations do not know that to become perfect, they have only to apply

themselves to this celestial norm. On the contrary, they seek perfection

only in knowledge and capacities, believing that the Perfect Ones know

everything, can do marvelous things, and that one should acquire each of

the numerous knowledges and capacities of the Perfect Ones. So one

forsakes the celestial norm, namely, the Moral conscience, one exhausts

oneself to investigate books, to scrutinize institutions, to compare the

vestiges of the Perfect Ones. As results, the more our knowledge becomes

widened, the more human desires are increased; the more our capacities

are increased, the more the celestial norm is obnubilated..."

Confucianism

recognizes two ideal types of man: The gentleman or superior man and the

Saint.

The Superior Man

or the Gentleman is he who takes care of his spirit and his

soul.(Mencius, VI, Pt. I. Chapt. 15)

He knows his high

destiny. (Analects XX, 3)

He has high

aspirations. (Analects XIV, 24)

He endeavors to

cultivate himself. (Analects XV, 17, 20; Doctrine of the Mean chap. XIV

& XX)

He likes to tread

on the path of virtue rather than on that of profit. (Analectd IV, 6 &

XV, 9)

He is

intelligent, adaptable, eager to learn. (Analects VI, 25 & IV 10.

Doctrine of the Mean, XX)

He prefers action

to words. (Analects XV, 23. V, 11- XII, 15)

He is always

composed, serene, and satisfied (Analects, IV, 1. VII, 36)

Mencius has

portrayed the Superior Man by these words: "To dwell in the wide house

of the world, to stand in the correct seat of the world and to walk in

the great path of the world; when he obtains his desire for office, to

practice his principles for the good of the people; and when that desire

is disappointed, to practice them alone; to be above the power of riches

and honors to make dissipated; of poverty and mean condition to make

swerve from principle; and of power and force to make bend: These

characteristics constitute the great man."

The Book of

Poetry has also praised the Superior Man as follows:

'Look at

those recesses,

In the

banks of the Ke,

With

these green bamboos,

So fresh

and luxuriant!

There is

our elegant prince,

As from

the knife and the file,

As from

the chisel and the polishes!

How

grave is he and dignified!

How

commanding and distinguished!

Our

elegant and distinguished prince,

Never can be forgotten.

Above the

Superior Man is the Saint, the ideal man, the achieved type of

perfection.

The Saint acts

always in conformity with his moral nature. His intelligence perceived

without effort the inmost cause of everything; he will experience no

difficulties at tending towards the goodness and at staying firmly in

the path of righteousness, order and duty. The Saint is in fact the

personification of God.

Therefore, man

should develop all his potentialities. An individual cultivates himself

to become a superior man, and then a sage, and then a saint. A Saint

takes God as his model, a sage take a Saint as his model, a superior man

will imitate a sage, and an individual will imitate a superior man.

Personal

cultivation begins with learning. It is with good reason that the Lun Yu

(Luận Ngử) opens with the following saying of the Master: "To learn and

to relearn again, isn't it a great pleasure?" Reminiscing about his own

lifelong course of cultivation, Confucius identified the starting point

thus: "At 15, I set my heart on learning; at 30 I was firmly

established; at 40 I had no more doubts; at 50 I knew the will of God;

at 60 I was ready to listen to it; at 70 I could follow my heart's

desire without transgressing what was right. "Education, teachers, and

even books have always been accorded great respect and attention in

China. Confucius was the great professional teacher of China, and he is

revered as the "Supreme Sage and Foremost Teacher".

When properly

understood and pursued, however, learning goes hand in hand with

practice. The famous "golden rule" pronounced by Confucius came in

answer to an inquiry by a pupil concerning conduct. The dialogue runs as

follows:

Tzu Kung (Tử

Cống) asked: "Is there any one work that can serve as principle for the

conduct of life." Confucius said: "Perhaps the word 'reciprocity': "Do

not do to others what you would not want others to do to you." (Analects

XV, 23)

In addition to

learning and practice, personal cultivation requires reflection, or

meditation. In the Lun Yu there is recorded the remark by one of

Confucius' immediate disciple, "I daily examine myself on three points"

(honesty in business transactions, sincerity in relations with friends

and mastery and practice of teachers' instructions). Later, Mencius

said: 'He who has exhaustively search his mind, knows his nature.

Knowing his nature, he knows God."

It would be a

failure on our part, if we would not deal with the Confucian political

theory, because Confucius has never rested only in the improvement of

the individual.

"The kingdom of

world brought to a state of tranquillity was the great object which he

delighted to think of; that it might be brought about as easily as "one

can look upon the palm of his hand" was the dream which it pleased to

him to indulge.

"He held that

there was in men an adaptation and readiness to be governed which only

needed to be taken advantage of in the proper way. There must be right

administrators, but given those, and "the growth of government would be

rapid, just as vegetation is rapid in the earth..."

"This readiness

to be governed arose according to Confucius from the duties of universal

obligation, or those between sovereign and minister, between father and

son, between husband and wife, between elder brother and younger, and

those belonging to the intercourse of friends.

"Men as they are

born into the world, and grow up in it, find themselves existing in

those relations. They are the appointments of Heaven. And each relation

has its reciprocal obligations, the recognition of which is proper to

the Heaven-conferred nature. It only needs that the sacredness of the

relations be maintained, and the duties belonging to them faithfully

discharged, and the "happy tranquillity will prevail all under

heaven..."

"With these ideas of the relations of

society, Confucius dwelt much on the necessity of personal correctness

of characters on the part of those in authority, in order to secure the

right fulfillment of the duties implied in them. This is one grand

peculiarity of his teaching...

Confucius said:

"To govern is to set things right. If you begin by setting yourself

right, who will dare to deviate from the right?" "Chi K'ang (Quí Khang

Tử) asked about government and Confucius replied: "To govern means to

rectify. If you lead on the people with correctness, who dares not to be

correct?" (Analects, XII, 17).

" Chi K'ang (Quí

Khang Tử) distressed about the number of thieves in the State, inquired

of Confucius about how to do away with them. Confucius said "If you,

Sir, were not covetous, though you should reward them to do it, they

would not steal." (Analects, XII, 18).

"Chi k'ang asked

about government, saying: "What do you say to killing of unprincipled

for the good of the principled? Confucius replied: "Sir, in carrying on

your government, why should you use killing at all? Let your evinced

desires be for what is good and the people will be good. (Analects, XII,

19).

"The relation

between superiors and inferiors is like that between the wind and the

grass. The grass must bend, when the wind blows across it." (Analects,

XII, 19).

As to the

institutions of government, Confucius endeavored to foster the

Theocracy, promoted by the ancient Sovereigns.

Theocracy is an

ancient form of government in which God is supposed to rule over all the

people, through the agency of a Holy Sovereign, called Son of God. In

Theocracy, the king is God's vicar on earth; he is king at the same time

pontiff, and is the mediator between God and men.

He should be then

perfect, because he is really the Son of God, conducting people to

perfection by his teaching and his life.

He should select

wise, virtuous and capable ministers to help him governing people.

The government

should aim to take care of all people, to foster prosperity and

happiness, to instruct people and LEAD THEM GRADUALLY TO A PERFECT AND

HOLY LIFE.

The Great

Political Charter of Ancient China, now three thousand years old, was

reported to be inspired by God, to the Great Iu (2205-2197).

It contains nine

chapters. We sum up them as follows:

1). The Ruler

should know the properties of the elements in order to help all the

people to live properly.

2). The Ruler

should know how to cultivate himself, to fulfill himself, to become

intelligent, competent, majestic, wise and saintly.

3). The Ruler

should know how to govern his subjects. For this purpose, he should

fulfill eight duties:

1.

Provide food to people.

2.

Secure commodities for people.

3.

Foster religious duties of people.

4.

Secure the comfort of people dwellings.

5.

Teach people all their moral duties.

6.

Deter them from evil by a good organization of Justice.

7.

Regulate festive ceremonies and social intercourse for people.

8.

Secure the well-being of the State by having an efficient army.

4). The Ruler

should be informed about the movement of the celestial bodies, the

rhythm of the seasons. He should establish an accurate calendar in order

to harmonize the works of his subjects with the cosmic and seasonal

changes.

5). The Ruler

should be a living example of perfection and a spiritual guide as well

as a temporal guide for all his people.

6). The Ruler

should govern with correctness and straightforwardness. But he should

also know how to rule or strongly or mildly according to circumstances,

and people.

7). If the Ruler

has doubts about any great matter, he must consult with his own

intelligence; consult with the nobles and officers; consult with God

through the agency of divination.

8). The Ruler

should consider all the natural calamities as warnings of God concerning

his defective behavior or his defective government and amend

consequently.

9). The Ruler

should consider the happiness and extremities of the nation as

reflecting faithfully his own attainments and defects in reference to

people. In fact, a good government will result in prosperity,

healthiness and high moral standard in the nation. A bad government will

result in calamities, illness and high frequencies of delinquencies in

the nation.

In brief, love,

cooperation, trustfulness, respect for human dignity are the framework

of this ideal Theocracy.

"The celebrated

passage in the Li Chi (Lễ Ký), sometimes referred to as the Confucian

Utopia, begins with the following pronouncements: "When the age of the

Great Tao prevailed, the world was a community of all people. Men of

virtue and talent were upheld and mutual confidence and goodwill were

cultivated."(Li Chi - Lễ Ký, Li Yun - Lễ Vận)

James Legge has

summarized the ancient Chinese creed and the ancient Chinese Theocracy

as follows:

"The name by

which God was designated was the Ruler, and the Supreme Ruler, denoting

emphatically his personality, supremacy, and unity... By God, kings were

supposed to reign, and princes were required to decree justice.

"All were under

law to Him; and bound to obey His will. Even on the inferior people, He

has conferred a moral sense, compliance with which would show their

nature invariably right. All powers that be are from Him. He raises one

to the throne and put down another. The business of Kings is to rule in

righteousness and benevolence, so that the people may be happy and good.

They are to be an example to all in authority, and to the multitudes

under them. Their highest achievement is to cause the people

tranquillity to pursue the course which their moral nature would

indicate and approve.

When they are

doing wrong, God admonishes them by judgments, storms, famine, and other

calamities. If they persist in evil, sentence goes for against them. The

dominion is taken from them, and given to others more worthy of it."

Thorton in his

History of China, observes: "In my excited surprise and probably

incredulity, to state that the Golden Rule of our Savior: "Do unto

others as you would that they should do unto you", which Mr. Locke

designates as "the most unshaken rule of morality, and foundation of all

social virtue" had been inculcated by Confucius, almost in the same

words, four centuries before."

I quote again

James Legge : "But I must now leave the sages. I hope I have not done

him injustice. The more I have studied his characters and opinions, the

more highly have I come to regard him. He was a very great man, and his

influence has been on the whole a great benefit to the Chinese, while

his teachings suggest important lessons to ourselves who profess to

belong to the school of Christ."

Confucian Mysticism

Up to now, no one

has talked about Confucian mysticism. Confucius can be called a mystic,

but when he speak about himself, he is very brief, and use very humble

terms.

The highest

Confucian mystics, mentioned by Confucius and Mencius, were Yao (Nghiêu;

2357-2255 BC), Shun (Thuấn; 2255-2205 BC), Iu (Đại Võ; 2205-2197), King

Wan (Văn Vương; 1258-? BC), and Woo (Võ Vương; 1122-1115 BC). (The works

of Mencius VII, part 2, 38)

The life of these

Holy Sovereigns is described in the Shoo King, or the Book of Historical

Documents (Kinh Thư, and in the She King, or the Book of Poetry (Kinh

Thi).

We know that in

these ancient times, people endeavored to become perfect and to be

united to God, and believed that God was very close to everyone.

In the Great

battle in the wilderness on Muh, that confronted the troops of Woo, and

those of the tyrant Show, to galvanize the faith of the King in God, the

Grand Master Shang Foo (Trọng Phụ) thus said to King Wu (Võ Vương):

"The

troops of Yin-Shang (Ân Thương)

Were

collected like a forest,

And

marshalled in the wilderness of Muh.

We rose

[to the crisis];-

'GOD IS

WITH YOU,' [said Shang-Foo to the King],

'HAVE NO

DOUBTS IN YOUR HEART.'

The

wilderness of Muh (Mục Dã spread out extensive;

Bright

shone the chariot of sandal;

The

teams of bays, black-maned and white-bellied, galloped along;

The

grand-master Shang-fu (Trọng Phụ)

Was like

an eagle on the wing,

Assisting King Woo (Võ Vương),

Who at

one onset smote the great Shang (Thương).

That morning's encounter was followed

by a clear bright [day].

At this ancient

time, people believed that God illumined their heart, to show them the

way of wisdom, so that they could have the same virtue of God. It is

said in the She king:

The

illustration of illustrious [virtue] is required below,

And the dread majesty is on high.

At this period,

The Holy Sovereigns believes that God descends in their heart.

Therefore, they never relaxed in the maintenance of their virtues. It is

said in the She King:

Full of

harmony was he in his palace;

Full of

reverence in his ancestral temple.

Out of

sight he still felt as under inspection,

Unweariedly he maintained [his virtue].

King Wan has

attained a high degree of perfection, and became an expression of God,

therefore he was named King Wan. Wan means in fact expression. It is

written in the She king:

'The

doings of High heaven,

Have

neither sound nor smell,

Take

your pattern from King Wan,

And the myriad regions will repose

confidence in you.'

At this time,

people believed that following the way of their ancestors was following

the true religion of God, and the true filial piety.

It is

written in the She King:

Ever

think of your ancestor,

Cultivating your virtue,

Always

striving to accord with the will [of Heaven].

So shall

you be seeking for much happiness.

Before

Yin lost the multitudes,

[Its

kings] were the assessors of God.

Look to

Yin as a beacon,

The great appointment is not easily

[preserved].

It is said also:

This

King Wan,

Watchfully and reverently,

With

entire intelligence served God,

And so

secured the great blessing.

His

virtue was without deflection;

And in consequence he received [the

allegiance of] The States from all quarters.

At this time,

all the great people liked to live in conformity to God's will. This is

called leading a holy life. In brief, at this time, people understand

already what is mysticism, and what does it mean by Union with God.

Confucius rarely says that he is a mystic, that he has realized Union

with God, except only one time, when his life was endangered, when he

was surrounded by the people of K'wang. Then he declared himself an

expression of God, exactly as King Wan. He said: "After the death of

King Wan, was not the expression [of God] conferred to me? If God had

wished to led his expression perish, then I should not have such an

honor. While God does not let his expression perish, what can the people

of K'wang do to me?"

Mencius called

mystics men who practiced the Doctrine of the Mean, that I have

retranslated as The Eternal Center. In this book, Confucianists pretend

that mystics followed the natural path of perfection, written by God in

the hearts of all people. Mencius added that only in about 500 years,

can one find a Mystic. He gave us also a list of Chinese Mystics in the

last chapter of his book. (J. Legge, The Works of Mencius, pp. 501-502)

To become a

mystic, we must believe that the nature of man is good. The Goodness of

man is proclaimed by Confucius, and especially by Mencius.

In the beginning

of the Doctrine of the Mean, It is said: "What God has ordered us to

realize is called The Nature. An accordance with the Nature is called

Religion. The regulation of this Religion is called Instruction. The

Religion cannot be left even for an instant. If it could be left, it

would not be the Religion." So the true Religion is to follow our own

Nature, and the injunctions of our nature are written in our conscience.

For Confucius,

the true religion springs forth from the inmost of our heart. It is said

in the Doctrine of the Mean: "The religion of the superior man is rooted

in himself, and sufficient attestation of it is given by the masses of

the people. He examines them by comparison with those of the three

kings, and finds them without mistake. He sets them up before heaven and

earth, and finds nothing in them contrary to their mode of operation. He

presents himself with them before spiritual beings, and no doubt about

them arise. He is prepared to wait for the rise of a sage a hundred ages

after, and has no misgivings..." (Doctrine of the Mean, Chap. XXX, 3).

Mencius is

categorical in affirming that the nature of man is good. "The tendency

of man's nature to good is like the tendency of water to flow downwards.

There are none but have this tendency to good, just as all water flows

downwards." (J. Legge, The works of Mencius, Book VI, Part I, 2, p.

395).

It is said in the

Shoo king:

The

Human Self is restless and changing,

The

Divine Self is very recondite.

Realize

purity, Realize Oneness,

Stick to

your Central Self.

(J. Legge, The

Shoo King, The Counsels of the Great Wu, 15 p. 61. Translation of the

Author)

In that case, man

has two hearts, or two minds: A Carnal mind or Human self, full of

passions, and a Divine Self, or a Spiritual Mind very simple, and pure.

It is our Central Self, which gears us in our way to perfection.

To find out this

Central Self in our self is the beginning of our Mystical way. It can be

also called Illumination, or Conversion, or rebirth of the Spirit. To

orient our self from our Carnal mind to our Spiritual mind is to tread

on the Celestial pathway.

To get rid our

self of our Carnal Mind, is to become a Saint.

The whole human

pathway is then cyclical, half of it is called Human life; another half

is termed Divine Life. The first half is dominated by extroversion, the

second half is dominated by introversion or introspection. The middle of

our life is then around 35, or 36 years.

It is said in the

I Ching: "One Yin and One Yang is called Religion, if you can follow

this path, it is good. If you can follow this path up to its end, you

will realize your Nature. (The I Ching, The Great Treatise I, chapter 5,

1.)

Confucius also

said: "My religion is that of an all-pervading unity... Tsang (Trang Tử)

said: The religion of our master is to realize perfection in our heart,

and to render other people similar to us" (Analects, Book IV, 15)

Confucius has get

rid of his carnal mind. It is said in the Analects: "There were four

things from which the Master was entirely free: He has no foregone

conclusions, no arbitrary predetermination, no obstinacy and no egoism.

(J. Legge, Analects, Book IX, 4, p. 217)

We must repeat

that the Doctrine of the Mean is the book that teaches people the

Mystical Way. In its first chapter, a commencement is made with the

mention of God as the conferror of man's nature, while in its last

chapter, the progress of man in virtue is traced, step by step, till at

last it is equal to that of God. "A Saint, or Confucius, can be compared

to heaven and earth, in their supporting and containing, their

overshadowing and curtaining all things; he may be compared to the four

seasons in their alternating progress, and to the sun and moon in their

successive shinings."

We finds also

that in the period of Sung (960-1279), there is a philosopher, called Lu

chiu Yuan (Lục Tượng Sơn; 1139-1192) who taught a monistic system of the

mind which was the legislator of the universe. He was also a mystic.

Convinced that

"Truth is nothing other than the mind and the mind nothing other than

the truth" and that "the Six Classics are but footnotes of my mind," Lu

chiu Yuan did not emphasize book learning and did not write a single

book himself. Condemning the method of extension of knowledge through

investigation of things, he believed that spiritual cultivation

consisted of contemplation - looking inward into one's own mind - and

sudden enlightenment.

In presenting

Confucianism, I try to give all its main characteristics, but I can not

be exhaustive. I didn't give the lectors its evolution through the ages,

because I realize that people don't understand Confucius' ideas yet, so

I endeavor to emphasize some aspects of Confucianism, such as its

relationship to God, its way of understanding man, its way to govern

man, so that man can have a virtuous life.

I like

Confucianism because it does not have an organized body of clergy.

In Confucianism,

man can find God inside himself, and needs no help from any clergy.

It does not have

any external cult for God, and tries only to live according to the

injunctions of the moral conscience. (J. Legge, The Doctrine of the

Mean, Chap. I, 2,3. Analects XII, 4)

In our study, I

have lead you in the profundity of the mind, pretending that only there,

you can find the source of your life, and the mainstream of all your

energy. God is there, and all the highest motivation of men spring forth

also from there.

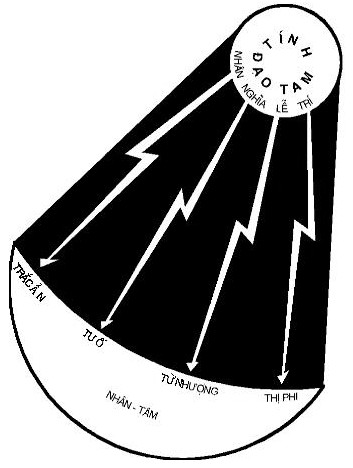

In my study of

Confucianism, I have devised two diagrams, one depicting the soul of an

ordinary man, and the other depicting the soul of a saint.

In the first

diagram, The Xing (Tính Đạo Tâm) of man, or the Divine Self of man is

represented by the Sun. It is perfect in itself and contains in

perfection all the four cardinal virtues: The Principle of Benevolence

(Nhân), the Principle of Righteousness (Nghĩa), the Principle of

Propriety (Lễ), and the Principle of Knowledge (Trí).

The Xin (Nhân

Tâm) or the Human Self, is represented by the Moon. It has in itself the

Feeling of commiseration (Trắc Ẩn) derived from the principle of

Benevolence, the Feeling of Shame and Dislike (Tư Ố), derived from the

principle of Righteousness, the Feeling of Modesty and Complaisance (Từ

Nhượng), derived from the principle of Propriety, the Feeling of

Approving and Disapproving (Thị Phi) derived from the principle of

Knowledge. Exactly as the moon receives its rays from the sun, The Xin

(Tâm) receives all their feelings from the Xing (Tính). These feelings

are then imperfect and inadequate.

The Divine

Self and The Human Self

Legend:

Đạo Tâm: Divine Self

Tính: Nature

Nhân: Principle of

Benevolence

Lễ: Principle of Propriety

Nghĩa: Principle of

Righteousness

Trí: Principle of Knowledge

Nhân Tâm: Human Self

Trắc Ẩn: Feeling of

Commiseration

Tư Ố: Feeling of Shame and

Dislike

Từ Nhượng: Feeling of Modesty

and Complaisance

Thị Phi: Feeling of Approving

and Disapproving

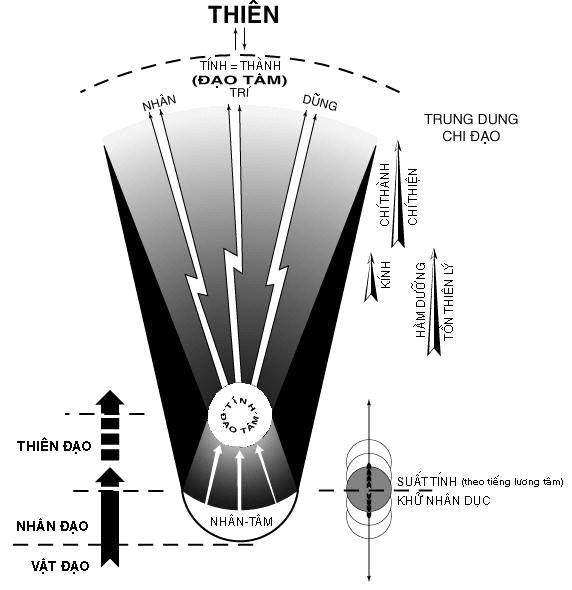

Physical Duty, Psychological Duty and

Spiritual Duty

Legend:

|

Thiên : |

God |

Trung Dung Chi Đạo: |

The Religion of The

Principle of the Mean |

|

Đạo Tâm : |

Divine Self |

Chí Thành, Chí Thiện: |

Driving up to

perfection |

|

Tính, Thành: |

Nature, Divine Self |

Suất Tính (Theo tiếng Lương

Tâm): |

To follow our own

Nature or Conscience |

|

Nhân: |

Principle of

Benevolence |

Khử Nhân Dục: |

Conquer our passions |

|

Trí: |

Principle of Knowledge |

Kính: |

In reverence to the

Godhead within us |

|

Thiên Đạo: |

Spiritual Duty |

Hàm Dưỡng: |

To keep our mind clean |

|

Nhân Đạo: |

Psychological Duty |

Tồn Thiên Lý: |

To keep all the

celestial norms |

|

Địa Đạo: |

Physical Duty |

Nhân Tâm: |

Human Self |

Now if we go to

the second diagram, we see immediately that we must change the direction

of our lives. We must go now from our Xin back to our Xing, to realize

our Divine Self. We must then make a Conversion. This Conversion can be

called also the Rebirth of the Spirit. This change in the sense of our

life can be also called the Introversion Way or the Instrospective Way.

We can see now that the way of a plain man is diametrically opposed to

that of a saint. The one is extrovert, the other is introvert. We can

say that all saints are introvert. (J. Legge, The Works of Mencius, Book

II, chap. 6, pp. 201- 205)

We learn also

from Confucius a great lesson that, without effort, we cannot realize

anything good. Furthermore, being a human being, and living in this

immense and beautiful world, we cannot lead a lazy life, but we should

strive to something more beautiful, and more useful

We should find

out in our self our divine nature, and try to realize it in our life.

This Divine Nature is the Tai Chi (Thái Cực), or the Ens Realissimum or

The Xing (Tính).

We should find

out all the natural laws that govern all the aspect of our life,

physically, physiologically, mentally, spiritually (J. Legge, the She

King, Decade of Tang, Ching min, p. 541.)

We should obey

all the natural laws that help us to bloom all our potentialities. (J.

Legge, The She King, Odes of Pin, Fah ko, p. 240)

We should become

poets, always living with nice ideas, with nice dispositions of our

soul, knowing how to find out and to enjoy all the natural beauties.

We must know how

to live in harmony with the cosmos, with every man, and everything.

(Analects VIII, 9)

We should be

responsible for everything good or bad, happening in our life, and in

the life of our nation. If all of us live properly, and cooperate with

each other, our political and economical life will be prosperous; if

not, we will live miserably.

Confucius teaches

us that we have three kinds of duty:

1). Physical duty

(Địa Đạo, Vật Đạo): We must improve our environment, our material life.

2). Psychological

duty (ren tao, Nhân Đạo): We should live properly, and behave properly

with each other.

3). Spiritual

duty (Tian dao, Thiên Đạo): We should cultivate our spirit, progressing

to perfection, and live in union with God. (R. Wilhelm, the Yi Jing, Ta

Chuan, The Great Treatise, Chapter X, 1, pp. 351-322

But now, as

people do not yet evolve enough to follow the spiritual duties,

therefore Confucius is very brief about it. (Analects III, 12)

In short, we

don't find in Confucianism, any superstition. It teaches us only what is

natural, what is true. (J. Legge, the Doctrine of the Mean, Chap. XI).

Since the XVIIth

century, Confucianism has been attacked, by Catholic missionaries who

tried to present it as atheistic, and recently by Mao-tse-Tung who likes

to supplant it.

Missionaries came

in China at the beginning of the XVIIth century, and were full of

prejudices against Chinese people. They regarded them contemptuously,

and considered them an inferior race.

"They (the

missionaries) despite the "yellow races" of the Orient; tried to convert

these inferior beings and, at the same time, told each other, in print,

and even told them to their face, that they were so brutish, so

contemptible, that they were hardly worth converting. "Chinese

civilization" wrote a distinguished missionary priest in the middle of

the 19th century, "is a monstrosity, not only anti-Christian, but

anti-human..." The religions of the Chinese are monstrous, absurd, the

most ridiculous in the world. "One does not find humanity, he concluded,

among the people of the Orient, but only "monkeydom."

"The Chinese,

being by nature inferior to the European, will always be inferior as a

Christian."

"All the

missionaries will love the Chinese for the love of God and for the sake

of their soul; we will devote our self to them, on supernatural

principles; but friendship!; that is impossible."

Missionaries

sustained that Confucianism is atheistic, that Confucius himself was

damned, with all other Chinese ancestors who were all atheists and

idolaters.

"In his twenty

first question, Navarette asked if Gentiles, i.e. non Christian Chinese

who live a respectable life (non nimis laxe, sed aliqualiter modeste

viventes) could be saved?

"Some

missionaries" he said, meaning the Jesuits, have denied this

proposition". The Holy Office replied: "Those who teach that these

Gentiles are not punished with eternal suffering contradict the Holy

Scriptures". Answering the 22th question, the Holy Office affirmed that

Infidels dying without baptism, or without having had a real desire for

baptism, were damned".

"The priest of the Foreign Missionary

Society announced that "Confucius was damned to eternal flames." The

Holy Office replied: "Allowing for what has been said, it is forbidden

to say that Confucius is saved."...

Navarette

however, reinforced in his opinions by these decisions, declared, five

years later, that since "Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Pliny, Seneca, etc,

were irretrievably damned, how much more Confucius, who was not worthy

to kiss their feet."

In sum, the

missionaries' strategy can be resumed as follows:

a). Admission of

some compromise, showing some respect to Confucian morale, agreeing that

T'i, or Shang T'i. or T'ien means God, accepting the ancestral cults of

Chinese people. This is the way of Jesuits but is rejected by the Roman

Catholic church.

b). No compromise

at all. Destroy Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, as perverting religions

and promulgate the Catholic faith. This is the policy of all the other

missionaries. The Roman Catholic Church follows this view.

As for

Mao-Tse-Toung, he taxed Confucianism of feudalism, and tried to supplant

it in China.

"The victory of

Communism in 1949 and the Cultural Revolution of 1966, have meant a

break with tradition that is far more profound than anything that has

happened in China since the unification by the Ch'in (Tan) dynasty in

221 BC. Confucianism, whether as a state cult or as an organized system

of belief, is now a thing of the past in its homeland, though it still

has professed adherents in the latter sense on Taiwan and elsewhere

outside the Chinese People Republic (e.g. among Chinese living in

Southern Asia and North America.)

Communist rule in

China has put an end to all free inquiry and established Karl Marx's

system of dialectical materialism as the state philosophy.

Today, most of us

have a more enlightened view of China, and yet some misconceptions

remain. The key to understand China lies in the ability to focus on key

problems rather than in the memorization of endless data.

Today, also,

Chinese studies are pursued by many students in many universities in the

West. The cultural interest behind this development may be traced to

such modern philosophers as John Dewey and Bertrand Russell, Ernest

Francisco Fenelossa (an American Orientalist), and Esra Pound, poet and

translator of Confucian Classics.

Confucian

Classics are translated in French and English by many scholars such as

P. Regis, Zottoli, Leon Wieger, Seraphin Couvreur, J. Legge, Richard

Wilhelm. Such interest means that Confucianism can never be destroyed,

because it tries to discover all the natural laws or Li that are behind

all human behaviour.

Cf. James Legge, The Shoo King, The Counsels of the Great Wu, 15.

Gaubil says:- 'The heart of man is full of shoals (ecueils); the heart

of Taou is simple and thin '; and adds in a note:'The heart of man is

here opposed to that of Tao. The discourse is of two hearts,- one

engaged in passions, the other simple and very pure. Tao express the

right reason. It is very natural to think that the ideas of a God, pure,

simple and Lord of men, is the source of these worlds.'

Translated from French, Henri Bernard Maitre, Sagesse Chinoise et

Philosophie Chretienne, p. 133. Nouveaux memoires du P. Lecomte,

parus en 1696.

Quran, Al-Baqara, verse 187.

Udana,

80-81, ibidem p. 95: apud R. C. Zaehner, Mysticism Sacred and Profane,

p. 126.

Le Nirvana et le Samsara sont aussi l'un a l'autre, comme l'eau et les

vagues. Nirvana c'est l'etre (et la buddheite) dans l'etat de

permanence. Samsara c'est l'etre (et la buddheite) dans l'état

d'impermanence. Le Nirvana c'est l'eau; le Samsara c'est la houle. Le

Nie-p'an c'est l'etre absolu le reste Cheng-Seu est l'apparence. Dans

l'ocean du Nie-p'an permanent, nous sommes des rides impermanentes.

Sortir de l'impermanence pour entrer dans la permanence, c'est

Kie-t'ouo, la delivrance.

The Great Learning, III, 4

Thọ Văn Nguyễn, The Doctrine of the Mean, p. 165, note 1.

Les Jesuites avaient entrepris cette Evangelisation sur une échelle

cyclopedienne et s'étaient dressés contre les autres missions

catholiques, franciscaines, capucines et dominicaines, qui toutes

croyaient en la politique de la table rase cad en l'absence totale de

compromis avec les cultures et modes de pensées de l'étranger. Selon

cette doctrine opposée à celle des Jésuites, les missions chrétiennes

devaient tenter de convertir les masses et détruire de fond en comble

les civilisations paiennes...

TOC |

Preface | Chapters:

1 2

3 4

5 6

7 8

9

10 11 12

13 14

15

16 17

18 19

|